It’s hard to believe I’ve been running white grub efficacy trials for this long, but since I’ve started wrangling the data generated from these efforts, some interesting patterns have begun to emerge.

I’d like to share these data as I’m able to get them summarized and chopped into bite-sized chunks, and this article marks the beginning of those efforts.

Insecticide programming is a combination of logistics and the application of scientific information. Everyone has their favorite products and approaches, but operational constraints often dictate how much flexibility professionals have in developing their programs. Over the last few decades, the preponderance of long residual, systemic insecticides have provided even greater opportunities for turfgrass professionals to manage white grubs effectively. Not only are these products excellent insecticides, but the extended application windows provided by their residual activity allow for applications to be made over a longer period of time while maintaining very high efficacy against grubs. The end result has been a dramatic shift toward preventive grub control.

This shift away from IPM is understandable given the environmental characteristics of modern grub insecticides and the increasing pace at which we go about our daily business. But, it’s worth mentioning that some of our most effective grub insecticides do not require a preventive approach. I don’t expect everyone to scout for grub infestations, and make application decisions based on what they find. However, wouldn’t it be nice to know, with confidence, the potential trade-offs between efficacy and application strategy?

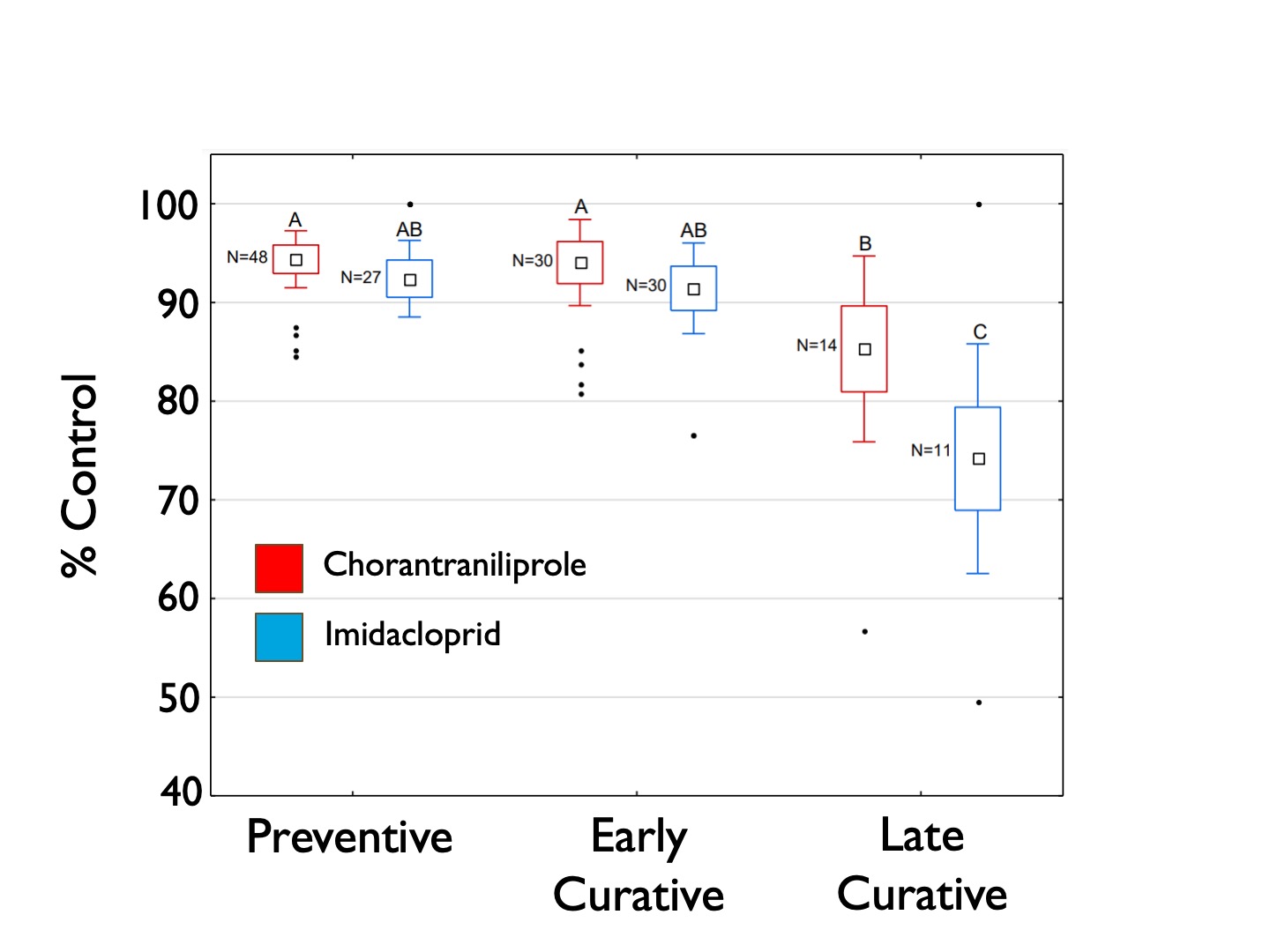

I’ve taken a subset of the data we’ve generated over the last 20 years to examine how application timing (think strategy) influences the efficacy of the two most widely used grub insecticides; imidacloprid and chlorantraniliprole (Figure 1). For our analysis, we considered applications made during May and June as preventive applications ¾ well in advance of the time white grubs are hatching from the eggs. Applications made during July and August were considered early curative applications and were typically made after egg hatch, but prior to the appearance of late instar larvae in the soil. Lastly, applications made during September and October were considered late curative applications and were directed toward late instar larvae.

When controlling for variation in application rate, imidacloprid, and chlorantraniliprole performed equally well when used in a preventive or early curative strategy, and there was no relationship between efficacy and application date during these two application windows. The average percent control was above 90% in both cases. Not surprisingly, we did see some decrease in efficacy for both active ingredients when used in a late curative strategy, with % control decreasing gradually the later these applications were made during the late curative window. What is most surprising is the relatively good performance of chlorantraniliprole when used in this fashion; with an average percent control registering at 85%. Even imidacloprid, registering 75% control during the late curative window, performed well against late instar grubs.

Remember, these data were not collected from just one efficacy trial, but from many replicated trials conducted over the last 20 years (N= the number of trials for each treatment). The bottom line is that while preventive applications tend to perform very well, the performance of early curative applications was indistinguishable. This means the time frame for good grub control effectively runs from May to September when either of these two materials are used, and that good control can be achieved much later than we often think. Something to keep in mind as you plan for the coming season.

Figure 1. Influence of application timing on the efficacy of chlorantraniliprole and imdacloprid against white grubs in turfgrass. Preventive = May-June, Early Curative = July-August, Late Curative = September-October. N = the number of replicated field trials including each treatment (material x application timing).